Anishinaabeg art-making as falling in love

Reflections on artistic programming for urban Indigenous youth

Masters dissertation submitted for Master of Arts in Indigenous Governance, University of Victoria

Ahh, Anishinaabe “art.” The soft blanket that has always kept me warm in the city. Tuning the radio to find the channel where my ancestors sing and laugh. Pulling paint across canvas to create beautiful worlds that glimmer in my eye and reside in my heart. Why do I call it art when it is like breathing, when it is like dreaming, when it is like singing and dancing and simply being?

Anishinaabe art is an expansive and limitless dance between self and world, self and ancestors, self and relations. Through art, we are able to weave our communities within our web of creation in accountable and loving ways, building the worlds we want to exist within. Art is both the root of Anishinaabe governance systems and the branches that reach upwards to touch stars, to house our ancestors and to sing into the great beyond. Within this expansive territory of Anishinaabe artistic practice, I carry forward my own personal relationship to art that is embedded within my experiential knowledge as a cis-gendered, heterosexual, able-bodied Anishinaabekwe artist and scholar who grew up away from my homeland. My exploration of Anishinaabe art always emanates from my own body and heart. In the broadest sense, this paper explores my relationship to artistic practice as an Anishinaabekwe attendant to my personal experiences and knowledges. I place this relationship at the heart of my approach to the development of arts-based programming for urban Indigenous youth.

Throughout this paper, I will discuss my community governance project, a component of my Master’s degree in the Indigenous Governance program. My project involved the creation of the Indigenous Youth Residency program at the Art Gallery of Ontario, an arts-based program for urban Indigenous youth that was approached through my Anishinaabekwe understanding of art-making in the context of settler colonialism and decolonization. Using the term urban can mean a lot of things. In the context of this project, I use the term urban to signify that this work was attendant to the diverse and multifaceted relationships that Indigenous youth have to the territory governed by the One Dish One Spoon Treaty in Tkaronto. Too often, urbanity is conveyed as antithetical to Indigeneity thereby erasing Indigenous presence and governance from urban spaces. Cities are Indigenous territories and urban Indigenous experiences are varied. This project sought to deconstruct the notions of urbanity that convey we are less Indigenous if we live in the city, instead working towards a practice of accountability through art- making that simultaneously strengthens relationships to homeland and the territories we reside on. Through my own understanding of Anishinaabe art as a practice defiant to the colonial compartmentalization of Anishinaabe life/art and Anishinaabe body/land, I disrupt our conceptions of the urban Indigenous through a practice of Anishinaabe art- life-body-homeland that makes spaces for realities of colonial displacement and agentive Indigenous mobilities and that foregrounds nation-to-nation relationships in the city.

It is also important for me to situate my work within an institutional context and in particular, within the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), a major art institution/corporation complex that perpetuates colonial myth-making and that forwards legacies of erasure, misrepresentation and exclusion. Developing and implementing the Indigenous Youth Residency program from within this space was no easy task. My identity as an Anishinaabekwe influenced how my labor and love were taken up within the institution. I will thus explore my experience working at the AGO as an Indigenous woman, both in an attempt to hold the institution accountable while also sharing insights that are hopefully useful to other Indigenous peoples doing important and challenging work within hostile institutional spaces. The last chapter of this paper is a stand-alone piece that explores the detailed methodologies and curriculum that were used during the Indigenous Youth Residency that may be of value to Indigenous communities seeking to engage youth through Indigenous artistic methodologies.

Anishinaabe art spills over boundaries. It oozes and overflows the rigid definitions of the gallery, is unreadable in its complexity, is threatening in its relationality, is deviant in the eyes of colonialism. Anishinaabe art denies containment and definition on all fronts and illuminates how these containerizations are a limb of colonial power. This paper honours the un-definability of Anishinaabe art and as such, I am not interested in prescribing characteristics or aesthetics of what Anishinaabe art can or should be. Rather, I am interested in celebrating how Anishinaabe art can overflow colonial boundaries, how Anishinaabe art creates space for individuality and autonomy and how Anishinaabe art is a radical love-filled practice of kinship that traverses nations, body, homeland and ancestors. Anishinaabe art, amidst its complexities and un- definability, is the creation of loving space for all our relations. My Anishinaabe understanding of art does not mean that I teach Anishinaabe art practices or even mutter the words Anishinaabe art but that I speak from where I come from and what I know and allow others to do the same. In this sense, the Indigenous Youth Residency program was not centered on Anishinaabe teachings but was approached and informed from my own relationship to art as an Anishinaabekwe. The participants of the Indigenous Youth Residency program were not all Anishinaabe nor were the different artists, Elders and knowledge keepers I brought in. In my Anishinaabekwe understanding of art, all of our approaches are valid and valuable and a large component of the program entailed the creation of space for the knowledge of others. The participants of the Indigenous Youth Residency program are my greatest teachers. I am so grateful to be a witness to their collective art practice that spilled over the boundaries of the gallery, exploding past boundaries of body and land, intricately weaving us all together in a radical act of love- filled kinship.

5- Year Old Anishinaabekwe: Born and raised in downtown Toronto. My Anishinaabe father, mobile and transient, shows up on our doorstep twice a year if I’m lucky. He’s tall, brown, has long braids and never seems to age. I don’t resent him yet and am still ecstatic when he shows up, content to roam the streets with him selling his art on the corner of Spadina and Bloor. Our world is bacon and eggs, stories of time travel and the people from the stars, moving, always roaming...

My mother is Scottish, English and Irish. When I am 5 years old, she is only 25 years old, the age at which I now write this paper. Even when I am young, I notice how I am chubby and brown and soft and that she is thin and angular and muscular and beautiful. Swiss Chalet for Christmas dinner is one of my favorite memories. Late hours, long hours, she’s always working to make it work.

My Nanny is the fire. English and Irish with red hair and piercing blue eyes. I am always with her. She is the punched-a-cop-in-the-face woman, pull-you-away-from-cartoons-to- smudge-woman, takes-you-to-Santeria-church-every-week-woman, helps-to-raise-my- brothers woman. Grandpa is close too and lives in our basement. Fiercely Scottish, tough to the bone plumber who carries bathtubs on his back. I watch him drill his thumb half- off and not even flinch. He loves me more than anyone ever has, I think. They both immigrated over to Canada when they were in their 20’s. They go to rallies. Mom and Dad met at a rally for Oka at Queen’s Park.

All the while, I am writing, I am drawing. I am alone often- in more ways than one- and I sit in silence and write poetry about time, fragile time. I carry myself away through the pictures and words that build worlds around me.

Throughout this paper, I share with you some details about myself that are normally considered extraneous to academic writing. I am following in the footsteps of Indigenous feminists who have long advocated for self-location as academic practice. As Métis scholar Zoe Todd (2016) reminds me, in order to ethically position myself within the professional, academic and personal spheres I walk through, it is imperative that I invite you to understand who I am and where I come from. Beyond providing important identity markers that situate my knowledge (that I am cis-gendered, heterosexual, able-bodied Anishinaabekwe with Scottish, Irish and English ancestors), I also share moments, fragments and seeming banalities that I feel are significant to my project and to the transmission of knowledge within this paper. This ongoing genealogy not only situates my knowledge, it also serves to honour my family, friends and ancestors as contributors to this project (Hilden & Lee, 2010, p. 58). Further, I have found that literal and didactic writing has failed me in the context of this project. Attempting to write academically about Anishinaabe art can disrupt the relationality inherent to our art processes (Pedri- Spade, 2014, p.75). Throughout this paper, I thus rely on academic, creative and visual modes of knowledge transmission that better encompass the murkiness (brilliance) of Anishinaabe art-life-body-homeland. I employ my own shapeshifting skills that are necessary to disrupt the supposed dichotomies I embody as Anishinaabe/academic, colonizer/colonized, teacher/student and artist/scholar (Hunt, 2014, p.28).

My practice of self-location is rooted in Anishinaabe protocol and when this practice is situated within the academic realm, it is also an act of sovereignty that celebrates my own experiences as valid sources of knowledge. I bring forward experiential knowledge that includes spiritual, body and land-based knowledges that may be inaccessible and unreadable to some readers by virtue of the relational and consent- based nature of these knowledges. I find that visual representations can serve as the best trickster shapeshifters, allowing some viewers access to certain knowledges while also having the ability to completely obscure and guard other knowledges. Importantly, by bringing forward my intimate experiential knowledge, I am celebrating the knowledges that live within my own body. At the heart of my project was the notion that we carry our homelands and the teachings of our ancestors within our bodies. As such, I rely heavily on invisible citations of body, citations of homeland and citations of ancestors and I have rejected the urge to insert academic citations where they did not truly inform my thinking on that matter. During my undergraduate degree, I was taught to insert citations fruitfully (or it wasn’t academic enough) and through disjunction (no relationship to the work was necessary, just so long as the citation works). This paper employs a relational approach to my practice of citations that demands I have a meaningful relationship either to the author or to the body of work I am citing. Further, I employ my own Indigenous feminist citational politic, one that prioritizes the voices of Indigenous women-identified people, two-spirit, trans and non-binary people whose voices are marginalized within academia and within our communities. On this note, this paper was also written to honour these people. My words are guided from and lovingly echoing back to the Indigenous women and two-spirit people who have already given me so much and to the youth I have been so privileged to learn from. These words are for you and many of them will be lost on others.

18-year old Anishinaabekwe: I am on my own. Made it to Vancouver, far from home but that’s how I wanted it to be. I will spend the next 5 years on Musqueam, Tsleil-Wauthuth and Squamish territories, but I will only really start to understand where I am when I am about 21, when I finally build up the courage to walk into the longhouse at UBC. Current Anishinaabekwe raises her hands high to the Musequam, Tsleil-Wauthuth and Squamish peoples for hosting her as an uninvited guest on their beautiful territory and for guiding her to find some of the most important people in her life.

18-year old Anishinaabekwe meets Taylor. In the coming years they will softly guide each other out of abusive relationships and will lean on each other, require one another, soul mates. Finding refuge in one another, they travel in one long thread that will never break. And then comes Olivia, quiet one who teaches me how to always care for others, how to be the unfaltering one, the one who is already a mother in so many ways. These two know me so well that I learn the hardest lessons from them. They even get to see stone cold Anishinaabekwe weep.

21-year old Anishinaabekwe meets Salia, the weaver of people, the weaver of women. She weaves a disparate group of native women together with threads of love and tears and witnessing. We find that so many of us have white mothers and native dads, broken native dads who perhaps could not love us fully and we laugh and celebrate ourselves that despite it all, we are here.

I meet Keisha, gentle strength, quiet strength, something brewing inside of her. When we look at each other we see it all, when we look at each other we see each other’s ancestors. When we look at each other, our ancestors feast together, share stories and plan the futures that are to be birthed from our friendship.

I meet Caolan, the one who perhaps words fail. He is the center and kwe has never had a center. He initiates the heart-breaking process of kwe coming to love herself. He bathes her body with a cool towel on a hot humid evening and cares for every part, holds her when she needs to pause and weep, collects the water and tears that fall from her body, walks so deliberately out to the river under the moonlight and slowly returns the healing water to the river kwe comes from.

Ultimately, my project arises out of an Indigenous feminist methodology that demands I speak from, and give validity to, my own experiential knowledge. I spent a lot of time reflecting on my experience as a young urban Anishinaabekwe growing up in Toronto and Fergus and decided to directly speak back to this experience. I thus came to my project through a desire to create a program that would have benefited me as a young kwe who heavily relied on artistic expression as a means of interacting with the world but who never got to access this kind of programming. My experience directly set the parameters of my community governance project. I knew that I had to return to the city of Toronto, that I needed to directly engage with urban Indigenous youth and that my means of doing so would be through artistic practice. After multiple recommendations from friends, I approached Wanda Nanibush, Anishinaabekwe force to be reckoned with, curator and community leader. She was moving into an official role at the AGO and decided to negotiate a place for me within the AGO to do my proposed project. It is important that I situate the beginning of my project with the admittance that I did not intend to do this work from within a large institution but rather ended up at the AGO by virtue of my desire to work with the ever-fierce Wanda Nanibush. In fact, as a young Anishinaabekwe growing up in Toronto, the AGO had never been a welcoming place for me and the first time I stepped foot in the building was for this project. Later in this paper I will discuss my institutional navigations and the necessity to resist the cooptation of my work. The AGO did not seek me out. The Indigenous Youth Residency program at the AGO is attributed to the labour of Indigenous women, and right from the outset we claim our labour fiercely and whole-heartedly.

17-year old Anishinaabekwe: Final year of high school in Fergus, Ontario. There is no one else like me here. I float in a sea of white. I talk to my Dad more now, he even comes to visit. Somewhere along the way, perhaps too young, I have had to carry the painful stories he holds. I know every detail about the residential school, about the theft of his humanity, the theft of his capacity to love, robbed of the ability to simply exist in the world fully. Pain from abandonment shifts to rage, a focused rage. This rage has quietly burned inside of me all throughout high school. In grade 9 art class I finish my first full painting of acrylic, airbrush and string. All of these figures erupting out of a swirling center. In grade 10 history I patiently wait to learn about the residential schools, to have my pain carried by others. It never comes, mentioned in a passing sentence. Nothing of the rape I know of, nothing of the loss, nothing of the starvation and mysterious operation scars. I want to yell out, he was only 8 years old! In grade 12 I create the Aboriginal Club, it is mostly one enthusiastic teacher and myself. My Dad comes to visit and we decide to fill in the gaps that grade 10 history hid. We grow stronger from this.

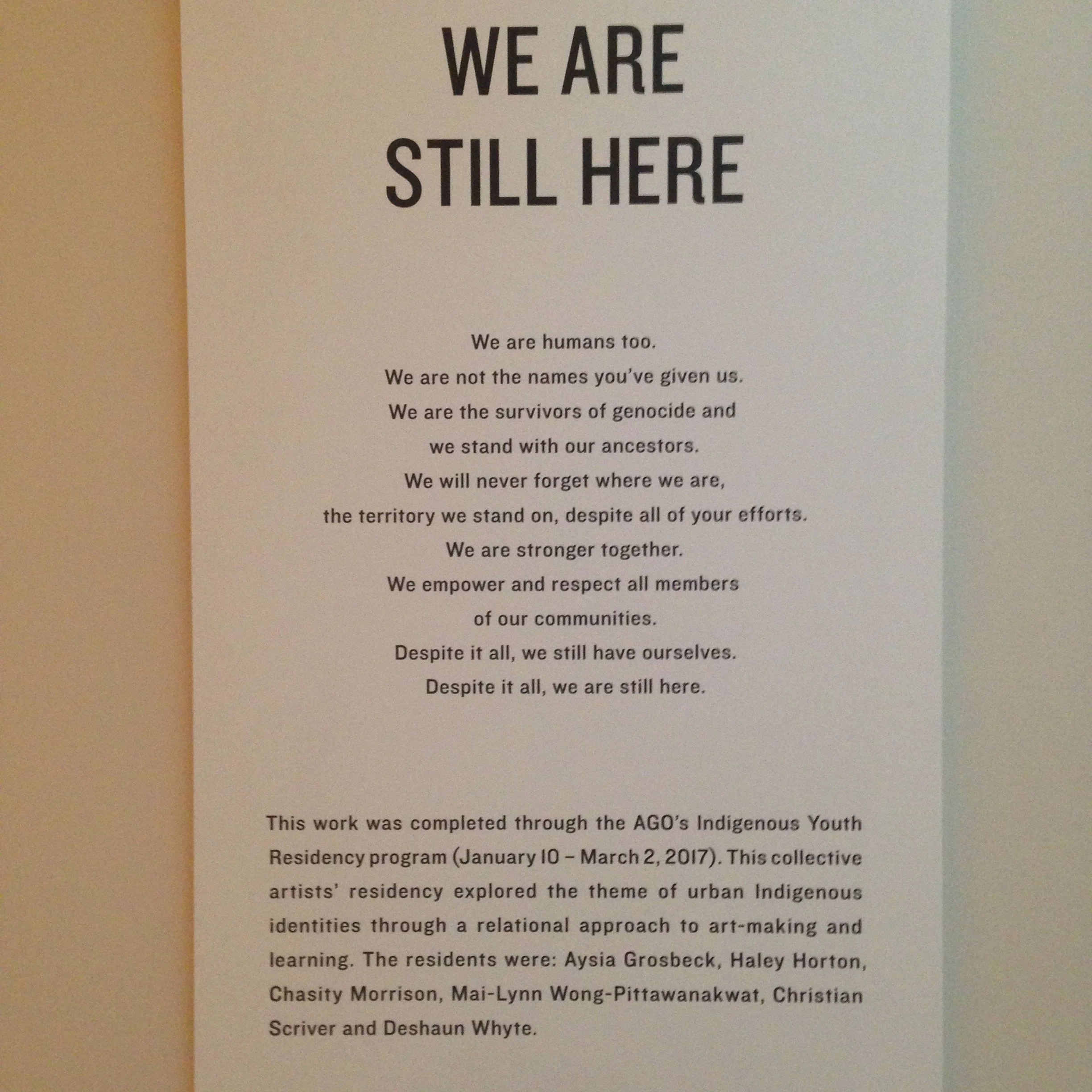

The Indigenous Youth Residency program hired 6 urban Indigenous youth between the ages of 12- 24 to participate in an 8-week residency program that required us to meet twice a week for two hour sessions. 30 people applied for the residency and I interviewed 24 applicants, selecting 6 youth who ended up being in the age range of 13- 21. Each resident was paid $15.00/ hour and I situated the program as an artist residency that included a collaborative final project that was celebrated in Walker Court and that was exhibited afterwards in the community gallery at the AGO. In this sense, the youth who were hired were delighted to announce that they would be doing a paid artist residency at the ever-exclusive AGO. The theme of the residency was urban Indigenous identities and we worked through a relational curriculum.

Broadly, this paper explores the creation of the Indigenous Youth residency program at the Art Gallery of Ontario. To begin, I would like to elaborate and explore my Anishinaabe approach to art-making that celebrates Anishinaabe art-making as governance and as a rebellious force that denies the compartmentalization of Anishinaabe life/art/body/homeland. Secondly, I would like to explore the false boundary between Anishinaabe body and homeland in the context of urbanity and displacement, working towards an Indigenous conception of belonging premised on an expansive notion of kinship that takes into account the agency of our ancestors. I would like to situate all of this work within the institutional context through a discussion of my experience as an Anishinaabekwe seeking to embody these concepts within programming for urban Native youth in a major art institution. Lastly, I will provide a succinct stand-alone exploration of my methodologies and curriculum that I hope will be useful to others. The teachings from this experience make my heart soar. Chii miigwech to my greatest teachers Aysia Grosbeck, Chasity Morrison, Christian Scriver, Deshaun Whyte, Haley Horton and Mai- Lynn Wong-Pitawanakwat. You are the reason I was able to carry on with this challenging work. It makes my heart so full to know that you are our future.

24- year old Anishinaabekwe: It is my first time spending an extended period in my homeland. Treaty 3 territory is so beautiful and I think about tracing my ancestors’ footsteps. It is the summer before I am to start my project at the AGO. We are meeting my father to go wild ricing. Ron always manages to look exactly the same, brown, tall, long braids. But he is not alone, he has come with a woman named Carol. She is brown, small, sturdy, strong. They speak fluent Anishinaabemowin to each other and I am in awe. We spend days sleeping on my grandmother’s floor near mitaanjigamiing. I marvel at the ways Carol disappears for extended periods of time, returning with medicines. She moves through the world like my father. One day she walks into the woods and comes back with a rock. It is a lightning rock and she tells me how special it is and gifts it to me. Carol gave us many gifts.

Months later, weeks into the Indigenous Youth Residency, the youth and I have gathered to make family trees. We know each other well, we are family by this time and we hold no shame. Young kwe doesn’t know her grandmother well but the name Carol escapes her lips, a similar description. I remember Carol telling me she lost her daughter and young kwe has lost her mother. That feeling as if all of your ancestors have been waiting for the punchline and they now chuckle deep into their bellies. I tell her all of the stories, promise to bring them together. At the end of the program, I give young kwe the lightning rock.

Anishinaabe life as art and Anishinaabe body as homeland

Being in Full

Omnipresent Anishinaabekwe has never felt the compartmentalization in her body, but she feels it projected at her, attempting to make her readable through the separation of her being. She has always felt the soft hands of ancestors, heard them whisper in the night. They have made her laugh out loud at times at the gifts they give her, the purpose they feed her, the joy in knowing how close they are, watching, waiting. Omnipresent Anishinaabekwe feels her own body, can shrink into a piece of floating dust and visit her homelands in the night, feels them ache with the weight of what they carry. City Anishinaabekwe has always known she carries her homelands in her body and this keeps her oh so warm at night.

The foundational logic of settler colonialism is that of compartmentalization. This compartmentalization creates the binaries, dichotomies and hierarchies that stand in stark contrast to the interconnections, complexities and intricacies that make up Anishinaabe life. Compartmentalization seeks readability, homogenization and categorization as prerequisites to the creation of hierarchies and individualism, the building blocks of settler systems of white supremacy, heteropatriarchy and capitalism. Compartmentalization attempts to contain us but we have always spilled over the boundaries. The veins of our bodies dig roots that traverse settler boundaries, our limbs become rivers that flow to lake and sea, and our minds reach up to the sky exploding past the ageist, ableist, heteropatriarchal, racist and capitalist settler normative ordering of the world. They are always trying to contain, sort and control us but we have always existed in pluralities and interconnections that render us incomprehensible, unreadable and deeply unsettling to colonial logics. At its core, settler compartmentalism/colonialism seeks to remove Indigenous bodies and minds from Indigenous homelands. This includes the physical removal of Indigenous bodies from their territories, acts of genocide that remove through death and assimilationist tactics that attempt to remove our minds from the belonging embrace of our homelands. Importantly, compartmentalization also seeks to cover settler colonial tracks, to render invisible the ways in which we are complexly dispossessed, to obscure settler colonialism as the culprit of our diverse colonial predicaments. This is the insidious side of compartmentalization where we may find ourselves unable to see past the boundaries that enclose us. When we look at settler colonialism through the lens of compartmentalization we begin to see how it is an obscuring force that seeks to enclose us within the boundaries of shame. Shame emanates from the legacy of colonial violence and lives within our bodies, minds and hearts (Simpson, 2011, p. 13). This context forms much of the basis for my work with urban Indigenous youth in which I seek to use my knowledge and privilege to help them see past the boundaries and separations around them, tracing routes of dispossession and mapping resistance, resiliencies and futurities.

Settler compartmentalization is also multi-scalar. It functions across scales that encompass physical body and land, as well as permeating our intimate, relational and spiritual realms. I am interested in a multi-scalar approach to resisting settler compartmentalization that acknowledges the interconnectedness of material and intimate processes of decolonization and that places value in these intimate forms of decolonization that often stand unacknowledged in comparison to public, large-scale acts of resistance (Hunt and Holmes, 2015, p. 158). In particular, I am interested in what happens to our conceptions of decolonization and resistance when we dismantle the compartmentalization of Indigenous body from Indigenous homeland, illuminating how relational and “immaterial” work is, in fact, frontline defense work of our homelands and our nations. Indeed, there is a legacy within our communities of hierarchically placing public, frontline defense of land as something separate from the defense of certain Indigenous bodies who experience disproportionate levels of settler violence. In the words of Nēhiyaw scholar Erica Violet Lee, “Walk through my neighbourhood with me tonight and I will show you the stories of a thousand revolutions that will never be written” (2016). I see and value the intimate relational work we do in caring and loving for Indigenous bodies as fighting for our homelands and nations.

Interrogating the colonial compartmentalization of Indigenous body/homeland also centers the interrogation of heteropatriarchy as a necessity for Indigenous nationhood. Hunt and Holmes write, “Accounting for Indigenous expressions of gender and sexuality requires acknowledging that the ongoing colonial categorization of Indigenous peoples and their identities is integral to the denial of Indigenous self- determination” (2015, p.159). The colonial distinction of Indigenous body from land teaches me about heteropatriarchy as a key structural component of settler colonialism (Simpson, 2015) because only when bodies are considered separate from the land can we begin to categorize, recognize difference and create hierarchies. Only when bodies are considered separate from the land can we deny each person’s place within the web of creation that necessitates plurality, diversity and interconnection. When we conceive of body separated from homeland, we divorce land-based struggles from the safety of all members of our communities. In my conception of decolonization, I choose to foreground my resistance to the separation of Anishinaabe body/land and in doing so, I choose to ground decolonization in the interrogation of heteropatriarchy. Approaching Indigenous body as homeland in my work with urban Indigenous youth allows me to interrogate heteropatriarchy in an accessible way through the reminder that Indigenous bodies are homelands, too, and that our bodies, our genders and our sexualities are beautiful in all of their complexities.

24-year old Anishinaabekwe gathers with sacred sisters. The design, when it entered her mind, made her burst with laughter. She knew where it came from. They have gathered together to stitch the design onto skin, have called in the ancestors and they wait on the boundary between our world and theirs, they huddle and dance and murmur just below the skin. Sacred sisters have cued the Pallbearer (for the pain), Princess Nokia (for the badassery) and of course have v traditional materials on hand such as smudge, a loaf of bread, sour fruit juice berries from Whole Foods and most importantly, the absence of men. Katzie, Gwich’in, Anishinaabe ancestors join hands for a moment and laugh together at what they have orchestrated. Their wrinkled faces form the creases of our bodies and show us how to laugh in our bellies. The skin is stitched with a story, maps the routes of our homelands together, women’s hearts stitched together through important moment of bodily sovereignty, important moment of everlasting love, important routes of how to return to one another. We rejoice in our technologies that allow us to resist compartmentalization.

Pre-contact Anishinaabe art-making was so woven into our governance systems and ways of being that it never had to be distinguished as such. Settler colonialism and its attendant boundaries, hierarchies and categorizations necessitates that I explicitly return to, recollect and revisit Anishinaabe art as an expansive, diverse and interwoven element of Anishinaabe life that escapes this compartmentalization. My exploration of Anishinaabe artistic practice is focused on how art can overflow the boundaries colonialism has worked so hard to create in order to beautifully weave Anishinaabe art as life and Anishinaabe body as homeland. In a world of theorizations, we find true meaning when we approach concepts from within our web of relations (Simpson, 2011, p.52) and as such, my exploration of Anishinaabe art lives within my own web of relations. This discussion is very much rooted from my heart and my body and in discussing what is valuable or present in my conception of Anishinaabe art should in no way discredit or limit other explorations for indeed, Anishinaabe art cannot be contained or defined. The dichotomy between art and life has roots in capitalist logics in which art circulates as commodity and artist becomes an occupation within our capitalist context.

When we resist the false binary of art/life, we deny the separation of artistic product from artistic maker. Art can no longer be a truncated activity focused on the creation of an aesthetically pleasing final product but rather, art-making inherently becomes about process. This is not to say that Indigenous art cannot aim to circulate in the capitalist market or be aesthetically pleasing, but seeks to place value in the ways Indigenous art can and does center relationship building as artistic process. Nēhiyaw, Saulteaux and Métis artist Lindsay Nixon reminds us that Indigenous artists, particularly women and two-spirit people, are using principles of love and kinship to guide us into decolonial futures telling us, “Like my kin before me, I would argue that a project of Indigenous resurgence is nothing, is inanimate, without an ethics of love and kinship as a guiding principle” (2016). I interpret this as a way of placing decolonial value in Indigenous art practices that are attentive to radical and love-filled relationship building within our kinship systems. And so, when I say Anishinaabe art, I am inherently referencing a decolonial and loving creative practice of kinship and relationality. This type of process-based and relational art-making has always been at the heart of Anishinaabe art practices. Within my understanding of the Anishinaabe worldview, relationships are at the heart of everything we do for they are the way we interact with and influence the world around us. Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Simpson describes our web of relationships as starting from the self, emanating outwards to reach family, nation and the land (2011, p.109). Similarly, Anishinaabe artist and relative Celeste Pedri-Spade describes her artistic practice as a relational process that draws upon her relationships to self, land, ancestors, the creator, her family and the artistic medium (2014, p. 88) in turn allowing us to think, feel, look, listen and act (Pedri-Spade, 2016, p.48). For Celeste, art-making is something done with the whole body (2014, p. 75) and when we create art we are summoning the complexities of our kinship networks, of our web of relationships, into a process of creation to be shared with our communities. Anishinaabe art breathes life into the teaching all my relations.

Anishinaabe art, as a radically relational practice, has always served as an essential component of Anishinaabe governance. When we create art, we enact governance over the self that also extends outwards to the broader family, community and nation. Embodying Anishinaabe sovereignty on these personal, relational and familial levels is where collective sovereignty truly begins (Pedri-Spade, 2014, p. 93). Indeed, as an Anishinaabekwe, I often use art to enter into a moment of bodily sovereignty where I feel in control over my own representation and body, an often fleeting feeling in the context of gendered settler colonialism. This is where it all begins. We cannot begin to practice sovereignty on the level of the nation if certain members of our communities do not have bodily sovereignty. We must start with the self and then radiate outwards to our families, the microcosms of the nation (Simpson, 2011, p.115). Artistic practice is a realm of autonomy that allows us to explore what sovereignty of the self may look and feel like. In addition to being an act of personal sovereignty, art-making is also a form of storytelling and knowledge transmission that shapes our collective governance systems. Wanda Nanibush shares an Anishinaabemowin translation of resistance that is akin to being planted in the earth. Our ancestors form our root systems that nurture us and store for the future, the stems of the plant, “process the past here and now” (2012, p.4). I conceptualize Anishinaabe art-making as living within the stem of our plants, as a radically relational process that demands we access our relationships to our ancestors, homelands and spirit kin. The Anishinaabeg have always had ways to dance with our ancestors through ceremony, dream and song, but art-making remains a mode of communication that allows us to translate these ethereal and other-worldly experiences to our broader communities and nations. As art-making does not have to convey literally and didactically, it allows us to gaze upon our ancestors in the present, it allows us to root our governance systems in the knowledges of our ancestors. And so, I conceptualize Anisinaabe art as a practice of expansive kinship accountability that allows us to communicate knowledges from our relationships to each other, the self, our ancestors, our homelands, animal kin and spirit kin. Anishinaabe art is the creation of beautiful Anishinaabe futures and presents premised on accountability to all our relations.

As I try to communicate how Anishinaabe artistic practice allows us to access and communicate a diversity of knowledges to our broader communities and nations, I find myself drawn to explore these knowledges as Anishinaabe archives. By employing the word archive I am trying to convey a sort of ever-lasting reference point, an omnipresent knowledge base. I am aware of the connotations in relation to the colonial archives which have so violently erased, misrepresented and dispossessed Indigenous peoples. Anishinaabe archives speak back to these erasures and violences by presencing Anishinaabe knowledge as alive, embodied and in permanence. Anishinaabe archives exist in ferocity and omnipresence and have always challenged the physical colonial archive in its linearity and fragility. Anishinaabe archives live within our homelands and our bodies, interchangeably, simultaneously, incomprehensibly. Importantly, Anishinaabe archives and their attendant knowledges are accessed through active relationships that demand consent (Simpson, 2014, p.15) and as such, they are not readable through non-consensual consumption of our bodies.

To my mind, Anishinaabe archives entail two components. The first is memory and the second relates to the content of these memories. When I think about what Anishinaabe memory means to me, I find that the term memory has too many linear connotations. Anishinaabe memory is not just about remembering and looking to the past, it is simultaneously about being in the present and projecting to the future. Anishinaabe memory thus exists outside of the confines of linear time, existing in a sort of liminal place beyond the structures that comprise our reality. So what exists within this place beyond time? What fills up these memories? The answer, to me, is simple. It is here where our ancestors dance, revelling in their omnipresence, their immediacy and their absolute permanence. Beyond the façade of linear time our ancestors breathe and plan, laugh and cook, love and care for us. And so I come to understand Anishinaabe archives as the knowledge of our ancestors that is only accessed through our embodied and consensual relationships to them. When I say ancestors I do not just mean those humans we have descended from, I also include clan relations, animal kin, spirit kin and place-based relations. When I say ancestors, I am invoking our expansive kinship networks and all of the relationships that have contributed to our existence in this moment. Further, when I say place-based relations I mean our homelands, both as an ancestral relationship and inclusive of all of the individual relationships that comprise this larger one. Importantly, when I say ancestors, I mean homelands too. It becomes hard to write about these things when the false separation of body/homeland/ancestors is so ingrained in our thinking but when I collapse these containerizations, I feel the warm embrace of my ancestors in my own body and I feel the lakes of my homelands softly rippling with a passing breeze. Anishinaabe archives are body and land. Our bodies are our homelands and we carry our homelands with us wherever we go. When we make art, we are summoning those relationships to the forefront and accessing these archives, we are beautifully remembering the tangibility of our ancestors and their immediacy, we laugh out loud at how close they are.

“If you want to know where to look

for them, hoping to catch them by surprise as they boil river water for their morning tea, lift one hand and trace the outline

of your spine.

follow the contours of hands and feet

as you step, memory by memory,

into the land of your body

where the dead lie waiting.”

From Land of the Dead, Gwen Benaway (2013, p.12) Accessing Anishinaabe archives can be a painful process in the settler colonial context. Before colonial occupation perhaps we did not distance ourselves enough from our archives to ever have to consciously think about accessing them. Settler colonialism has wrought multiple forms of violence that target the relationships that comprise our beautiful Anishinaabe archives. I think of my proximity to state-sanctioned genocide through my father’s experience in residential school and my current enmeshment within the now more insidious forms of colonial violence that threaten my existence. They tried to exterminate us and when that didn’t work, they tried to starve, rape and beat our archives out of us. They didn’t realize that you can’t remove these relationships from our physicalities, that you cannot break the bond between homeland and body, body and ancestor, ancestors and homeland. They cannot fathom the relational nature of our knowledge. But the violence takes its toll on our bodies and homelands and for many of us, our archives are enveloped in shame and locked in the confines of trauma.

Coming to acknowledge, remember and strengthen these archives is a painful process because it is a process of falling in love. When we fall deeper in love with our ancestors, they tell us that we have to fall deeper in love with ourselves and with our own bodies that have been marked as disposable and unworthy. When we fall in love with our ancestors, they wrap us in self-love and self-worth and we weep at how we may not have felt these things before. But, the deeper we love the stronger we become. The deeper we love, the harder we rage against the violence inflicted upon us by the settler colonial state. When I create art, I am falling in love. Sometimes, I am joyous and I relish in the gratitude and meaning that comprises my life. Sometimes, this is the most painful process for as I grow closer to the loving embrace of my ancestors, I carry the trauma, the legacy of genocide, the legacy of violence closer to my bones in my body. But always, falling in love is worth it. We deserve the right to fall in love with our own bodies and to feel the love exuded to us from our ancestors and homelands. As Erica Violet Lee beautifully speaks, “Allowing love to flow beyond the edges of our skin (in the form of touch), our lips (in the form of language), and our eyes (in the form of tears) is necessary and radical in a world where we’re taught to believe those borders are impassable” (2016).

Coming to love our urban bodies

Anishinaabe Archives in the City

14-year old Anishinaabekwe has brown skin and floats in a sea of small town white assholes. She finds the only other Native girl in Fergus, ON. They are inseparable for a while and they are mischievous. Maybe they find refuge in each other while also wanting to burn things to the ground. Shoplifting make-up at the walmart can get you cuffed, arrested and thrown in a cell for 5 hours even if you’re only 14 years old. Never to be friends again.

17-year old Anishinaabekwe goes to high school in Fergus, ON. The whitest town on earth. She is fetishized in every single intimate relationship she has. She is glaringly different, she is the Other. She is simultaneously WAGON BURNER! and GO BACK TO YOUR OWN COUNTRY! muttered from the same mouth. MY LITTLE SAVAGE muttered affectionately by another.

20-year old Anishinaabekwe is too nervous to study in the UBC longhouse because she feels like an outsider, like people can take one glance at her and tell she grew up in the city with a sporadic native dad. As if people can tell she went to high school in Fergus,ON. That she tried so hard during high school to fill in the gaps she experienced but that hosting an Indigenous gathering in Fergus meant sitting in a classroom with an overly enthusiastic teacher eager to learn.

As an urban Anishinaabekwe growing up off of my traditional territory, I speak from a position attuned to the complexities of urban Indigenous identities. In the city, authenticity narratives abound that create the dichotomies of on-reserve/off-reserve, city/homeland, assimilated/traditional rendering the city a particularly contentious place to assert one’s Indigenous identity. These authenticity narratives are carried forward by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and can prevent a sense of belonging while also contributing to the conception of urban cities as non-Indigenous, land-less spaces rather than as active Indigenous territories where culture, law and land are generative and living. In my work with urban Native youth, I constantly witness anxieties around a sense of belonging and identity, around feeling unable to contribute to their respective nations and in carrying a sense of shame for lacking cultural knowledge.

The prevalence of these authenticity narratives stem from settler colonialism as a form of governmentality that largely operates to remove Indigenous bodies from their homelands. Indeed, the ordering and organization of space according to the nation-state is foundational to the functioning of settler colonialism (Goeman, 2013, p.38). These colonial orderings of space such as the residential school and foster care systems, the pass system and the reserve system are just a few examples of the ways in which colonialism operates spatially to control, confine, erase or remove Indigenous bodies. These orderings, premised on colonial ideologies, further generate the hierarchies and binaries that support settler colonialism (Goeman, 2013, p.2). In my work with youth, I largely deal with the resulting dichotomies of reserve/city, traditional/assimilated and city/homeland. Importantly, these containerizations of Indigenous identity can prevent us from being able to see past our own boundaries. In the city, youth may find it easier to attribute a loss of culture, language and access to territory to their urbanity rather than making the larger connection to settler colonialism as a force intent on preventing Indigenous peoples from belonging to, and occupying, their homelands.

The act of talking unabashedly about our personal relationships to our territories speaks back to the hyperspatialization Indigenous peoples face and complicates the notion of place as a static site of identity formation (Goeman, 2013, p.10). Our relationships to our territories are diverse and multifaceted and cannot be relegated to the dichotomies settler colonialism creates. In this line of thought, I am drawn to think about my own relationship to the places I exist within and in particular, my father’s relationship to place. He has always been transient and mobile, drifting from Thunder Bay to Toronto to New York, frequenting friendship centers and managing to get around without a dollar in his pocket. This transiency was puzzling to me when I was younger but made perfect sense after he started sharing the stories of how our family travelled cyclically around our territories. In fact, our territory (or rather the routes my family would frequent) extended from Winnipeg, down to Minnesota and upwards towards Superior, overflowing the small reserve boundaries of Nezaadiikaang. Mobility is natural to my father and his mobility never threatens his identity as Anishinaabe.

I am drawn to think of the words of my friend Karyn Recollet who writes, “I am deeply interested in how the decolonial project calls upon Indigeneity to situate itself within traditional territory, and asks for a particular kind of land pedagogy that might not apply to us all, nor reflect all of our experiences” (2016, p.10). She reminds me of the privileges I carry. Even though I did not have the privilege of growing up on my territory, I carry the privilege of being able to visit my homelands, of carrying the stories of our territory through my father and of having the ability to move back to my territory in the coming months. Similarly, when I work with youth I am further humbled by my privilege. They remind me that even knowing where your territory is or what nation you come from is a profound privilege. They remind me that we must gather together and cultivate an Indigenous conception of belonging that takes into consideration realities of Indigenous displacement from territory and family while also making space for agentive Indigenous mobilities.

Combatting colonial geographies and dismantling harmful authenticity narratives around Indigenous identities means cultivating a new sense of Indigenous belonging in the city. Just as approaching identity through a strictly blood quantum approach is problematic and does not account for our multifaceted and contextual webs of kinship, approaching identity from a strictly physical requirement fails to account for the diverse ways Indigenous peoples relate to their territories through spiritual, emotional and mental realms. In her exploration of spatial discourses being (re)mapped by Native women, Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman “encourages us to move toward spatialities of belonging that do not bind, contain or fix relationship to land and each other in ways that limit our definition of self and community” (2013, p.11). Importantly, she draws our attention to creative practice and in particular, literature as a form that has the ability to profoundly unsettle colonial space in a complexity of ways (Goeman, 2013, p.2). Karyn Recollet similarly forwards creative practice- through hip hop and remixing- as a re- mapping that accesses the spatial cartographies and geographical scales that are denied to us through settler colonialism, allowing us to embody Indigenous scales of space/time that bind us to territories in radically decolonial ways (2016, p.92). In this sense, I see creative practice as having the profound ability to (re)map urban Indigenous futurities and presences and further, that this (re)mapping is an essential component of our nation building projects which must be attentive to our mobilities and displacements.

I am interested in looking towards our own bodies as maps to the decolonial future, as maps that are carefully crafted through the hands of our ancestors and as maps that contain a wealth of internal knowledge. I am interested in what happens when we remind youth of the archives housed within their own bodies. I conceptualize this approach as an extension of what Leanne Simpson forwards when she tells us that, “To survive as Nishnaabeg- we shouldn’t be just striving for land-based pedagogies, the land must once again become the pedagogy” (2014, p.14). My work with urban Indigenous youth reminds me that bodies are lands too and we have work to do in shifting our conceptions of belonging and identity to celebrate the internal knowledge of our ancestors and homelands that are housed within our own bodies. Land is pedagogy and also, body is pedagogy and so, when we use our bodies to create art we are engaging an Anishinaabe pedagogy that treats body and homeland as one in the same and we are, “creat(ing) a generation of land based, community-based intellectuals and cultural producers who are accountable to our nations and whose life work is concerned with the regeneration of these systems” (Simpson, 2014, p.13). We are, in the most profound sense, obliterating the colonial binary of body/homeland.

Accessing Anishinaabe archives in the city means celebrating our own knowledges and the relationships to ancestors and homelands we carry in our bodies. Embodying a body-land pedagogy does not just mean we get to turn completely inwards but rather, that we feel our bodies where they exist in time and space and engage with our internal knowledge as well as accountably relating to the territories we reside on. In this sense, a body-land pedagogy is as much about the body as it is about the land where one’s body resides and as such, demands we practice responsibility to the territories we are visitors on. Further, a body-land pedagogy does not discount the importance of material connections to homelands but rather, illuminates how we can practice accountability to our homelands even when we are away from them. We begin to cultivate an Indigenous conception of belonging that allows Indigenous minds to remain spiritually, mentally and emotionally accountable to homelands in the face of violent colonial displacement or agentive mobilities preventing physical connections. This conception of belonging acts as an empowering force to actually return to homeland, while also still acknowledging that returning to one’s territory can be a privilege many won’t receive.

Musings on Anishinaabe body-homeland-art-life:

When we collapse the containerizations of body from homeland, art from life, we

are left with a conception of art-making as a radical process of falling in love with our kin

rather than as a truncated activity oriented around the creation of an aesthetically pleasing

final product. Art-making is a way for us to access our archives or, in other words, art-

making allows us to dance with our ancestors, to listen to their soft words, to feel the

weight of our homelands in our bodies. This approach to artistic practice cultivates an

Indigenous conception of belonging that pushes back against the authenticity narratives

housed within urban spaces that tell urban Indigenous youth they are somehow less

Indigenous. We come to celebrate our bodies as carrying our homelands and our

ancestors while ethically engaging with the territories we may be residing on. When we

make art, we are falling in love and that is oh so beautiful.

On Indigenous women’s love and labor in the institution

I am one love-filled Anishinaabekwe

Anishinaabekwe floats around in huge, vast, white institution. She is marked through her body and marked through her labour. Kwe feels simultaneously underqualified-should- be-grateful-for-the-opportunity-intern and top-o-the-line-decolonization-expert-who- carries-the-weight-of-institutional-racism-on-her-back. One time kwe gives an hour-long presentation on Indigenous youth barriers to the AGO and afterwards a man comes up to her seeking her praise for having a conversation with another native person. He beams, “I just thought you should know that I talked to Quill for an hour last week and we had a great conversation.” I stare at him blankly and give him time to realize his mistake but he doesn’t. I tell him that in fact, I am Quill. I am the one who just gave you an hour-long interactive presentation, I am the one you uncomfortably share the elevator with every day, I am the one you fake a smile to in the hall. But hey, of course we are read and consumed not as the individuals we are but by the fact that we are Indigenous. Just Indigenous bodies who can serve settler purpose on a whim.

SECURITY CODE 1066: Be on alert for homeless people, deviants and trouble-makers.

I am one love-filled Anishinaabekwe. By love, I am invoking complexities and intricacies inherent to my identity as an Anishinaabekwe. By love, I mean a place-specific, body-specific, relational force that binds self to community, nation and homeland, nestling this bundle into the greater web of creation in accountable ways. Anishinaabekwe love is a force to be reckoned with, one that traverses, scales and obliterates the hierarchies and boundaries settler colonialism works so hard to maintain. Anishinaabekwe love, and actually the love of Indigenous women, two-spirit, trans and non-binary people, is so powerful that it has been an explicit target of settler colonialism since contact. Early settlers knew they had to destroy our love in order to separate Indigenous bodies from their homelands. Early settlers could see the ways our love binds our bodies seamlessly with our homelands, could see how it weaves our communities together in unfaltering intimacies.

Despite the genocide, the violence and the dispossession, we have continued to love. Sometimes, loving is a struggle. Sometimes, I struggle to love myself in a world that teaches me to think I am disposable, that wants me to forget where my homelands are, that wants me to feel like my ancestors aren’t there, watching, waiting and guiding. But yet, I continue to love. In fact, the relationship between my love and labour is a very close one and when I am most content is when my love and labour are synchronous. I have spent the last two chapters of this paper situating my work with urban Native youth as a radically relational, love-filled practice that embodies an Anishinaabekwe approach to art-making. At its core, this work emanates from Anishinaabekwe love for my community, love for my homeland and love for the youth I work with. Embodying this work within the Art Gallery of Ontario was challenging. My love as an Anishinaabekwe does not go unnoticed by the institution.

When I first started my work at the Art Gallery of Ontario, I was optimistic, energetic, hopeful and perhaps naïve. The love I carry as an Anishinaabekwe was made visible to the institution through my willingness to do, my willingness to stretch myself thin. Quite simply, when my love is readable and palatable to the institution, it is seen as a means to exploit labour from me. The labour of decolonizing the institution, the labour of institutional sustainability and the labour of translation can all be extracted from me when, out of love, I am seeking to make this institution a safer space for Indigenous people and in particular, for the Indigenous youth I am responsible for bringing into this space. I find myself in corporate board rooms about to give a 30-minute presentation to the department of Public Programming and Learning only to be squeezed in for the last 10 minutes. I find that not even my presence, but actually the possibility of an interaction with me through a presentation or a meeting, creates misplaced self-congratulatory celebrations within this racist institution. I start to feel less like a person and more like a fleeting Indigenous presence that serves to complicate the deep guilt of institutional racism. No one wants to actually do the work.

Anishinaabekwe is so tired. She goes to a meeting with the department of Public Programming and Learning and tells them she cannot run drop-ins anymore because she is only one person and because she needs the budget to run the Indigenous youth residency. She also tells them she will be paying youth who get accepted into the residency. She is met with hostility, is told to use her own honorarium to support the programs so that she can run both. Would this question ever be uttered to another person? Why do they feel so entitled to her labour? Does she need to remind them that they enforce an hourly workload on her honorarium such that she makes pennies? Does she need to remind them of all of the institutional work they have been putting on her shoulders? Does she need to remind them that ALL of kwe’s budget and honoria money comes from one donor specifically interested in kwe’s work? That the AGO literally doesn’t contribute a single cent to this work but yet feels entitled to it, consumes it, claims it...

Being a loving Anishinaabekwe within a major art institution is exhausting. I cannot help but feel that the entitlement to my labour is rooted in my identity as an Indigenous woman, as someone that settler colonialism perpetuates as less-than-human and as someone whose very specific love has historically been a target of settler colonialism. Anishinaabe scholar Dory Nason reminds us of the contemporary attacks on Indigenous women’s love in the context of the Idle No More movement reminding us that our love, “strike(s) at the core of a settler-colonial misogyny that refuses to acknowledge the ways it targets Indigenous women for destruction” (2013). Our love is oh so powerful. My love may have caused me to extend myself but it also crafts the boundaries of what I will and will not tolerate. My love is not just about giving, it is also about refusal. A point was reached at the AGO where my love became about uncompromising limits. They couldn’t understand why I valued a relational program. They couldn’t fathom why I wanted to pay the youth involved in the program an honorarium. Most importantly, they never stopped to ask why these things mattered to me. My love as an Anishinaabekwe became unreadable and incomprehensible to institutional objectives and I was quickly cast as deviant, rebellious and threatening. The art institution, a limb of colonialism, a pillar of capitalism, a machine of national myth- making, recognizes and knows that the boundless love of an Indigenous woman for her community is deeply unsettling to its very foundation.

After this breaking point, I relied on select individuals at the AGO to clear the institutional space for me to continue my work as it was intended to be done. If not for the presence of Wanda Nanibush and Andrew Hunter, both curators at the AGO, I am certain my work would not have continued. They both used their institutional privilege and positions to allow me to carry on with full autonomy and for this I am grateful. Acknowledging the necessity of Wanda and Andrew for this project is not only an expression of thanks, it also points to the fact that the AGO was not ready to support Indigenous programming, was not ready to accept that Indigenous programming is likely to be different from pre-existing institutional models, and was not even ready to listen from an Anishinaabekwe arts programmer willing to be so generous.

At the end of it all, I am still one love-filled Anishinaabekwe. But, I have learned important lessons both from the AGO and from the brilliant youth who participated in the residency. These youth have reminded me that it is just as important to love yourself as it is to focus on outward forms of love. They tell me that I must love myself more within these institutional spaces and that an Indigenous woman loving herself is the greatest threat to colonialism. In the context of the AGO, loving myself more means engaging in the practice of refusal when my labour is being exploited, a refusal to accommodate, a refusal to cede control, and a refusal to cushion settler feelings at the expense of Anishinaabekwe wellbeing. Most importantly, the youth have reminded me that loving myself within an institutional context means ownership and consent of my love and labour. In this vein, I will continue to defend, claim and celebrate my love and labour as an Anishinaabekwe. I will continue to be one love-filled Anishinaabekwe.

For Anique: Red and Black kwewag seek refuge in each other instantaneously by virtue of institutional racism. They gather in white spaces and create moments of safety and love. They know that if they let go of each other they risk being swallowed whole. They stand in front of each other, both a witness and look into each crevice of a wrinkled smile, every curvature of the limb, memorizing the maps of each other’s bodies, reciting each others’ stories knowing that this knowledge of one another is coveted, that knowing each other’s stories is a gift. Through their laughter they sonically map a future, can glimpse a place where they are safe and warm and free to simply be. Their laughter is so beautifully fugitive and it dances off of the walls of the hollow AGO rising to warm watching ancestors.

Exploring the development and facilitation of the Indigenous Youth Residency Program

Anishinaabe artistic methodologies

This section will explore an Anishinaabe methodology for working with Indigenous youth through artistic programming. In particular, I provide a methodological framework for Indigenous arts-based education and provide a detailed outline of the curriculum that was used for the Indigenous Youth Residency program that was implemented within the Art Gallery of Ontario. The Indigenous Youth Residency was an 8-week program that hired 6 urban Indigenous youth between the ages of 12-24. Participants met every Tuesday and Thursday evening for two hour sessions at the Art Gallery of Ontario and at SKETCH studio spaces. Each participant was paid $15.00/hour for a total honorarium of $480.00. The first five weeks of the program followed a relational curriculum that is explained in this section while the last 3 weeks of the program were set aside for studio time to complete a youth-directed, collaborative final project that was exhibited in the Community Gallery of the AGO.

Anishinaabe Artistic Methodologies

The following presents a list of guiding methodological principles that were utilized during the Indigenous Youth Residency program that could be applied to other arts-based programming for Indigenous youth.

1. The practice of ongoing self-location:

The practice of self-location is glaringly absent from arts-based education within institutional spaces where knowledge is instead truncated and distanced from the facilitator(s) such that what they provide is only related to the specific activity of skill- based art-making. In contrast, Anishinaabe artistic methodologies demand a deeper and continual process of self-location that honours the complexities and relationalities inherent to our knowledges. As a facilitator, I like to embody an Anishinaabe protocol of introduction as the starting point for any project. However, I am also selective about what I choose to share during a first introduction because I am cognizant of the ways in which introductions laden with cultural markers can be intimidating and disempowering for youth. This is why ongoing self-location is so important for it cultivates trust-building and becomes a continuous process that serves as the guiding methodological framework.

This practice of ongoing self-location as a guiding methodological framework is empowering for all involved. It encourages reflection while taking the onus off of participants to contribute their own personal histories. Simultaneously, speaking from the heart and from one’s personal experiences places value in every individual’s experiences and ensures knowledge transfer is non-hierarchical and non-authoritarian. Together, we come to recognize that many sources of knowledge are valid and we start to recognize the self, Elder, family and land as teacher (Chartrand, 2012, p.153). In this sense, an Anishinaabe methodology is attentive to different sources of knowledge and may incorporate elders, knowledge keepers and land-based pedagogies formally into the project. A practice of radical self-location generates a safe environment for reciprocal learning, utilizes a diversity of sources of knowledge and dismantles the compartmentalizing logic of colonialism that truncates our interconnected experiences.

2. Place-centered methodologies

Engaging a place-centered methodology in arts education starts with acknowledging your relationship to the territory. We must take seriously our obligations, as proponents of decolonization, to center the repatriation of Indigenous land or risk the metaphorization of our projects (Tuck and Yang, 2012, p.3). Quite simply, if we are not attentive to place then we are complicit in the erasures that facilitate ongoing colonial dispossession that are particularly rampant in institutional spaces. This process starts with a territory acknowledgement and if possible, prioritizing the participation and/or facilitation by elders, knowledge keepers and community members from the host nation(s). Most importantly, a place-centered methodology approaches art-making as an enactment of accountability that ensures the artistic practice honours our obligations and responsibilities as potential visitors to the territory.

Centering place within our methodologies is Indigenous protocol. This centering does not mean appropriating the host nation(s)’ teachings, but rather entails creating space for community participation and for dialogues on accountability to territory while honouring self-specific and nation-specific knowledge. This deep understanding of place, which includes an awareness of where you come from and where you operate from, is central to our knowledge systems and resists multiple forms of colonial erasure (Blight, 2015). This place-conscious methodology also maintains the integrity of our nation-specific knowledges (Chartrand, 2012, p.154). Place-centered methodologies may also entail physically engaging with the land itself. In Anishinaabe pedagogy, the land is both context and process, and knowledge flows through the diverse web of relationships we have (Simpson, 2014, p.7). Engaging with the land in both rural and urban contexts grounds our knowledge within our interconnected web of creation and speaks to a non- compartmentalized conception of art-making. Engaging with the land in urban contexts allows us to reclaim the city as a site for radical relationship building within our diverse urban communities (Recollet, 2016 p.100).

3. Let’s focus on relationships: A decolonizing relational artistic praxis

Decolonization must seek to strengthen, reclaim and restore the relationships that settler colonialism has sought to destroy. As Indigenous people, we have always honoured our relationships that extend not only to our communities but outwards to our non-human and spirit-based kin. From my Anishinaabekwe understanding, we are a relational people. Anishinaabe knowledge is inherently relational. Anishinaabe artistic practice is relational. Anishinaabe pedagogy is processed-based and subjective (Chartrand, 2012, p.154). When we make art we engage our whole bodies and nourish our relationships to the self, each other, to the medium we are using, to our ancestors and our homelands (Pedri-Spade, 2014, p.88). Relationships are the key to decolonization, both in returning to ourselves and in restoring the relationships that have been specifically targeted by settler colonialism. A radically relational praxis demands that we shape our artistic methodologies to strengthen all our relations.

This relational approach to art-making applies to both process and product. Our methodologies should prioritize the strengthening of relationships during art-making. These relationships are expansive and overflow the boundaries of what art is typically thought to be. We can practice accountability to our ancestors and our homelands through a relational artistic practice. We can strengthen relationships within our working groups while also exploring the intimate relationships we have to the inner self. Some specific methodologies that embody this relational approach include using the talking circle, using collaborative artistic projects that require negotiation and making room for discussions to explore how we relate to various components of creation. These methodologies are relational and thus center on process rather than product, which can be useful for youth or participants who are intimidated when there is pressure to make an aesthetically pleasing final product (Flicker et al., 2014, p.28).

4. Art education within the art institution

Institutional settings are complicated spaces for Indigenous peoples to exist within. Museums and galleries are often pillars of capitalism and colonialism, actively perpetuating nationalist narratives and colonial myths. Even radical approaches to museum pedagogies seem to fall short for the Indigenous visitor because the museum’s foundation in capitalism and loyalty to colonial narratives will never be compromised. Often, this results in the museum being a hostile and unsafe space for Indigenous people, particularly Indigenous youth. The hostility of the art institution is not just in the perpetuation of colonial narratives, the erasure of peoples altogether, the commodification of Indigenous pain and suffering, or the exclusion of Indigenous peoples from programming, but also within the ways Indigenous bodies are policed and put under rigorous surveillance in art institutions. For many, the museum remains unsafe.

For all of these reasons, I suggest an autonomous space model for working within institutions. This means that rather than attempting to weave Indigenous art methodologies into a pre-existing institutional framework for programming, we demand an autonomous space for our work to exist within. In simpler terms, it means... give us the space you owe us from profiting off of stolen lands and genocide and leave us alone. This will entail rejecting the labour of translation that will likely be burdened on the Indigenous person in the institution, instead advocating for the institution to relinquish its desire to control, understand and validate Indigenous arts education. An additional consideration for the Indigenous individual working within cultural institutions is to build practices of self-care into your conception of your role and responsibility within the institution. Just as the museum can be an unsafe space for the Indigenous individual, it can be very unsafe for the Indigenous employee seeking to embody a practice that cuts at the very foundation of the institution.

Week 1: Orientation and Introduction to Territory Accountability

This week was to orient youth to the program with the first session largely functioning as an ice-breaker session. Besides going over house-keeping details, these sessions were used to set the tone of the program as a professional artist residency, as a unique experience that participants should take full advantage of by coming prepared, which in turn made participants feel special and excited. Importantly, I used these introductory sessions to cover basic cultural protocols so that no youth felt as if they were culturally inept. I explained my teachings around smudging, prepared the youth with teachings around Elder protocols and Elder Pauline Shirt shared her teachings around water and around the role of the youth.

Tuesday Discussion:

● Talking circle for introductions and territory acknowledgment

● Creating a collaborative contract together

● Discussing program supports, having medicines available throughout and smudging to open and close each session

Discussing the complexities of operating within the AGO

Discussing elder and smudging protocols in preparation for Thursday

Bus fare and dinner were provided each session.

Week 2: Relationship to Self

This week was used to explore the most intimate relationship we have, the relationship we have to the self. We started our discussion with an overview of settler colonialism, brainstorming what colonialism means to us and understanding colonialism as a force intent on removing Indigenous bodies from Indigenous homelands. We discussed colonialism as a project of genocide. We then situated ourselves within the context of settler colonialism acknowledging how hard it can be to trace one’s own history of dispossession, as settler colonialism seeks to keep the knowledge of how we are dispossessed hidden. Rather than require the youth to share their own histories, I shared certain aspects of how colonialism has affected my life and we talked broadly about shame as something that is operationalized by colonial objectives.

Broad themes:

Situating ourselves in the settler colonial context

Self-care and self-love as radical resistance in the context of settler colonialism

Exploring emotional responses to colonialism: anger, love, shame, fear, pride

Goals:

To provide the tools for youth to articulate and identify their experiences of colonialism

To rid of colonial shame that may exist from gaps in certain knowledges

To contextualize feelings of anger and shame, and to provide productive artistic avenues to channel these emotions

To make clear that the goal of colonialism is to remove Indigenous bodies and minds from Indigenous homelands and that we should all celebrate our very existences

Week 3: Relationships to Each Other

This week we explored the relationships we have to each other within our diverse and multifaceted communities across axes of difference. In particular, we looked at how colonialism is gendered and heteropatriarchal and we will discuss how these notions become internalized within our own communities. We will discuss how women, queer, two-spirited, trans and non-binary people have historically and contemporarily been targeted through colonialism as people of immense power and knowledge in our communities. We will discuss how colonialism operates through the logic of compartmentalization and how we can resist this compartmentalization through artistic practice.

Broad Themes:

Understanding what internalized colonialism is and situating it in the framework of axes of oppression (racism, sexism, heteropatriarchy, etc.)

Exploring and articulating gendered forms of colonialism

Making the link between resource extraction and environmental violence and

gendered forms of colonialism.

Thinking of art as an enactment of accountability to all our relations and as an act of dreaming new realities that are inclusive and safe for all

Understanding that it is traditional to interrogate tradition when it oppresses us

Goals:

To cultivate a respectful, safe and empowering setting for all participants

To cultivate a ripple effect of respect for all our relations in our respective communities and nations

To empower youth to use art as a tool of resistance and resurgence to speak back

to injustices within the world and within their own communities

To make clear the centrality of the empowerment of Indigenous women, queer and 2-spirit people to projects of decolonization and resurgence

Let’s go over the axes of oppression that make up colonialism again. How are these internalized within our communities?

In particular, let’s focus on the axes of sexism and heteropatriarchy. Can we find a way to break down what heteropatriarchy means to us?

Indigenous feminisms and Indigenous sovereignty are inherently linked and Indigenous feminisms seeks to provide safety, support and honoring of all members of our communities.

Sharing histories of two spirit people from different communities. But also, we don’t need these histories to exist in order to demand accountability to all our relations in the present.

Sharing some of my story: feeling like bodily sovereignty is a fleeting moment at times, feeling the fear of one of my relations going missing ,the fetishization of our bodies, but also sharing about some of my relationships with Indigenous women and how badass they are.

Week 4: Relationships to Homeland

This week was used to explore and articulate our relationships to homeland in the context of living in the urban centre of Toronto. We began with an exploration of a territory acknowledgment, going beyond a simple recitation towards a personalized interpretation of what it means to live in these territories governed by the One Dish One Spoon treaty. We also discussed our own relationships to our homelands in a safe environment through the discussion on the spatiality of colonialism to illuminate how displacement from one’s territory is a product of colonialism and shouldn’t be a source of shame. In making connections between urban Indigenous experiences and settler colonialism, we collectively dismantled the narratives of authenticity that create the binaries of on-reserve/off-reserve, city/ homeland and traditional/ assimilated.

Broad themes:

Articulating an empowering understanding of urban Indigenous identities

Exploring accountability through mental, emotional, physical and spiritual realms, recognizing the ways in which we relate to place through immaterial ways and the ways in which we can practice accountability to our homelands through artistic practice.

Seeing the city not as a land-less space but a space where we can practice our relationship to the land.

Goals:

The empowerment of a diversity of urban Indigenous identities and ridding of toxic colonial identity politics

Providing a pathway forward through accountable artistic practices that put us into conversation with our homelands, communities and ancestors no matter how far away we may be from them

Cultivating a fluency in the ways in which colonialism operates spatially to remove Indigenous bodies from homelands, recognizing the reality of displacement and feeling good about

Prompts:

Recap of previous weeks: Understanding the intent of settler colonialism as seeking to remove Indigenous bodies from Indigenous homelands. We are not shameful. We recognize that any gaps in knowledge or culture are a result of colonialism and that it is not our fault. We celebrate ourselves through self-love and self-care. We acknowledge settler colonialism as a genocidal project. We understand that we have the right to challenge any tradition that oppresses us. We understand that we practice accountability to all our relations through artistic practice.

Whose territory are we on? Why is it important to acknowledge territory? Can we brainstorm a way to say a territory acknowledgement that resonates with us as a group? How about a territory acknowledgement through artistic practice?

Are we guests? Are we uninvited? Are we trespassers? Are we illegal occupants? What do these mean to us?

What does land mean to you? What does homeland mean to you?